Financial Account is a critical component of a country's balance of payments, tracking the intricate web of international investment flows that shape modern economies. For any business operating on a global scale, understanding the financial account is not merely an academic exercise; it is a vital tool for assessing a nation's economic stability, investor sentiment, and its integration into the world's financial system. This article will dissect the financial account, exploring its core components, its reciprocal relationship with the current account, and its profound impact on macroeconomic policy and business strategy.

This article outlines the key components of financial accounts to help businesses gain a clearer understanding of their structure, purpose, and practical applications. We specialize in services to help entrepreneurs register a company in Vietnam and do not provide accounting or investment advice. For specific matters related to taxation or financial reporting, please consult a qualified accountant or financial expert.

What is the financial account?

Financial account is a key component of a country's balance of payments (BoP) that records transactions involving financial assets and liabilities between residents and non-residents. It essentially tracks the net change in ownership of a nation's financial assets and liabilities, including direct investment, portfolio investment, other investments such as loans and deposits, and reserve assets, providing a clear picture of how international investment flows are financed over a specific period. These cross-border transactions involve a range of financial instruments, such as currencies, derivatives, equities, bonds, loans, deposits, and direct investments. By monitoring these flows, economists and business leaders can gauge the direction and volume of international capital.

- It is a core component of a country's Balance of Payments (BoP).

- It systematically records the net change in ownership of a nation's financial assets and liabilities with the rest of the world over a specific period.

- In simple terms, it tracks the cross-border flow of money for investment purposes, distinguishing it from money spent on goods and services (which is tracked by the current account).

- A surplus indicates that a country is selling more of its domestic assets (like stocks, bonds, and factories) than it is buying foreign assets. This means there is a net inflow of capital.

- A deficit indicates that a country is buying more foreign assets than it is selling domestic assets, resulting in a net outflow of capital reflecting investment abroad from the country.

Role of the financial account in the balance of payments

The financial account is far more than a simple ledger of transactions; it plays a dynamic role in the macroeconomic stability of a nation. Its position reveals how a country finances its relationship with the rest of the world and signals its attractiveness as an investment destination.

The financial account plays a dynamic role in the macroeconomic stability of a nation

- Its primary role is to reflect and finance the overall Balance of Payments, particularly helping to offset the Current Account balance. A country running a current account deficit, importing more goods and services than it exports, must fund this shortfall. It does so by attracting foreign capital, which is recorded as a surplus in the financial account. This inflow can come from borrowing abroad or selling domestic assets to foreign entities, including foreign direct investment, portfolio investment, and other investments such as loans.

- It serves as a key indicator of investor confidence in a nation's economy. A strong, consistent surplus often signals a stable political and economic environment that is attractive to foreign investors. Conversely, a sudden reversal from surplus to deficit (often characterized as capital flight or rapid withdrawal of foreign capital) can indicate deteriorating confidence.

- It reflects a country's level of financial integration with the global economy. High volumes of transactions, encompassing various types of investments, indicate deep and liquid connections to international capital markets. This integration allows a country to tap into a global pool of savings to fund domestic investment.

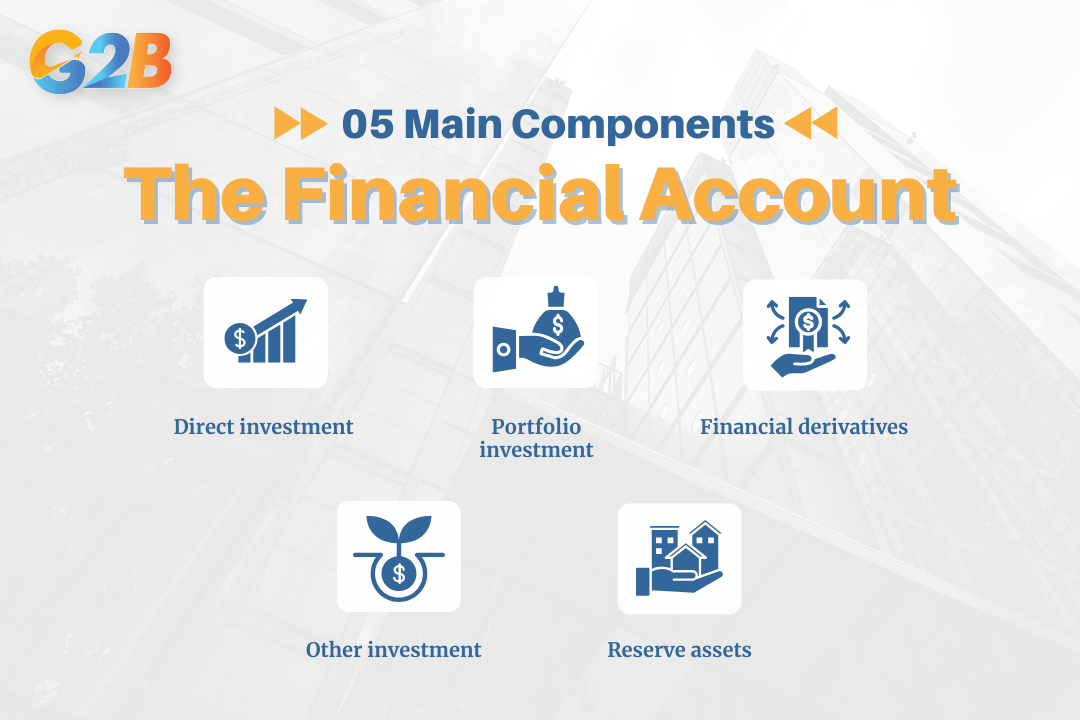

Structural components of the financial account

The financial account is meticulously structured to provide a granular view of different types of capital flows. It is broadly categorized into five main components: Direct investment, portfolio investment, financial derivatives, other investment, and reserve assets.

Direct investment

Direct investment refers to cross-border capital flows where an investor in one economy establishes a lasting interest in or a significant degree of influence over an enterprise in another economy. It is characterized by a long-term relationship and typically involves a substantial equity stake, often defined as 10% or more of the voting power. This form of investment is not merely a financial transaction but a commitment to participating in the management of the foreign enterprise.

Within the financial account, direct investment is considered the most stable and beneficial form of capital inflow. Unlike more liquid investments, direct investments are not easily withdrawn during periods of market volatility. They often facilitate the transfer of technology, managerial skills, and market access, thereby contributing directly to the productive capacity and long-term economic growth of the host country.

A classic example of foreign direct investment (FDI) is a foreign automobile manufacturer building a new assembly plant in a domestic country. Another example is a multinational corporation acquiring a controlling stake in an existing domestic company, integrating it into its global supply chain.

Portfolio investment

Portfolio investment consists of cross-border transactions involving securities, such as equities (stocks), bonds, and other negotiable financial instruments. Unlike direct investment, the primary motive behind portfolio investment is financial return, and it does not involve gaining significant influence or control over the foreign enterprise. Investors are passive stakeholders rather than active participants in management.

This component of the financial account is characterized by its high liquidity. Stocks and bonds can be bought and sold quickly on financial markets, making portfolio flows highly sensitive to changes in interest rates, exchange rates, and overall market sentiment. While these flows provide crucial liquidity to capital markets, their potential for rapid reversal, often termed "hot money", can introduce significant volatility into an economy.

A clear example of portfolio investment is a global investment fund purchasing shares of a company listed on a foreign stock exchange. Another common example is an international investor buying government-issued bonds of another country to capitalize on favorable interest rate differentials.

Financial derivatives

Financial derivatives are contracts whose value is derived from an underlying asset, group of assets, or benchmark. These underlying items can include stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies, interest rates, and market indexes. In the context of the financial account, these transactions record the buying and selling of such contracts between residents and non-residents.

The primary role of financial derivatives in international transactions is to manage and hedge risk. For instance, a multinational corporation may use a currency forward or options contract to lock in an exchange rate for future revenue or expenses, protecting itself from adverse currency movements. While they are crucial for risk mitigation, derivatives can also be used for speculation, which can amplify market volatility if not properly managed. (In some countries and reporting standards, financial derivatives may be partially recorded under the capital account or other financial categories rather than exclusively within the financial account).

An example of a financial derivative transaction in the financial account would be a domestic airline entering into a futures contract with a foreign entity to hedge against rising fuel prices. Another example is a resident investment bank trading interest rate swaps with a non-resident counterpart to manage its exposure to fluctuating interest rates.

Other investment

"Other investment" is a residual category within the financial account that captures all financial transactions not classified under direct investment, portfolio investment, financial derivatives, or reserve assets. It serves as a crucial catch-all to ensure that the balance of payments accounting is comprehensive.

Despite its residual nature, this category includes several significant types of capital flows that are vital for financing international trade and investment. It often encompasses a wide array of short - and medium-term financing that facilitates the day-to-day operations of the global economy.

Key examples of transactions recorded under other investment include cross-border loans from commercial banks, trade credits and advances between businesses, and holdings of currency and deposits in foreign banks. This also includes short- and long-term loans, currency and deposit accounts held across borders, and trade-related credits. For instance, if a domestic company receives a loan from a foreign bank to finance its operations, that transaction is recorded here.

Reserve assets

Reserve assets are external financial instruments that are readily available to and controlled by a country's monetary authorities, typically the central bank. These assets are held in foreign currencies and are used for specific macroeconomic purposes. They consist of assets such as foreign currency reserves (like U.S. dollars or euros), gold (classified as a reserve asset, not a typical financial instrument), and Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The fundamental role of reserve assets is to allow monetary authorities to finance balance of payments deficits, intervene in foreign exchange markets to influence the currency's value, and maintain overall confidence in the financial system. A substantial stock of reserves provides a buffer against external shocks and can help prevent financial crises.

A practical example is a central bank selling its holdings of foreign currency in the open market to purchase its own domestic currency. This action increases demand for the domestic currency, helping to strengthen its value during a period of depreciation. Conversely, it might buy foreign currency to prevent its own currency from appreciating too rapidly.

The financial account is broadly categorized into five main components

Correlative relationship with other macroeconomic accounts

The financial account does not exist in isolation. It is an integral part of the broader balance of payments framework, which is designed to be a perfectly balanced set of accounts.

Reciprocal relationship with the current account

The Balance of Payments operates on a double-entry bookkeeping system, which means that, in theory, it must always balance to zero. However, in practice, statistical discrepancies (net errors and omissions) often cause slight imbalances. This accounting identity creates an inverse and reciprocal relationship between the current account and the sum of the financial and capital accounts. The current account and the financial account are the two primary components, acting as two sides of the same coin.

A Current Account Deficit signifies that a country is spending more on foreign goods, services, and income than it is earning from them. To finance this shortfall, the country must have a corresponding Financial Account Surplus. This surplus is achieved by either borrowing money from abroad or selling domestic assets to foreigners, which represents a net inflow of capital. Essentially, a nation consuming more than it produces must fund this gap with foreign investment.

Conversely, a country with a Current Account Surplus is earning more from the rest of the world than it is spending. This excess income must be invested abroad, resulting in a Financial Account Deficit, which signifies a net outflow of capital. The country is effectively lending its excess savings to the rest of the world or acquiring foreign assets. It is important to note that the reciprocal relationship involves the sum of the financial and capital accounts rather than the financial account alone.

Clear distinction from the capital account

While historically the terms were sometimes used interchangeably, under modern IMF standards, the capital account is a separate and much smaller component of the BoP compared to the financial account. The capital account records very specific types of transactions that are non-market, non-produced, or do not affect national income.

The capital account primarily includes two types of transactions: Capital transfers and the acquisition or disposal of non-produced, non-financial assets. Capital transfers include items like debt forgiveness or the transfer of assets by migrants. Non-produced, non-financial assets include intangible assets like patents, copyrights, trademarks, and natural resource rights.

The distinction is crucial: The financial account tracks the vast majority of international investment flows related to financial assets and liabilities. The capital account, in contrast, is a minor ledger for specific and infrequent transactions. For most analytical purposes concerning international capital flows, the focus is squarely on the much larger and more impactful financial account, with the capital account playing a minor role.

Operational mechanism and economic impacts

The financial account functions according to precise accounting rules and has profound, often dual-edged, economic consequences. Understanding its operational mechanism is key to interpreting its data, while appreciating its impacts is essential for navigating the opportunities and risks presented by global financial integration.

Principle of capital flow accounting

The recording of transactions in the financial account adheres to the principles of double-entry bookkeeping, where every transaction has two offsetting entries. For clarity, the flows are recorded as follows:

- The system follows double-entry bookkeeping rules.

- Capital inflows are recorded as a credit (+). This occurs when a non-resident purchases a domestic asset (e.g., a foreign firm buys a domestic factory) or when a resident borrows money from abroad, increasing the country's liabilities. This represents money entering the country.

- Capital outflows are recorded as a debit (-). This occurs when a resident purchases a foreign asset (e.g., a domestic pension fund buys foreign stocks) or when the resident lends money abroad, increasing the country's claims on foreigners. This represents money leaving the country.

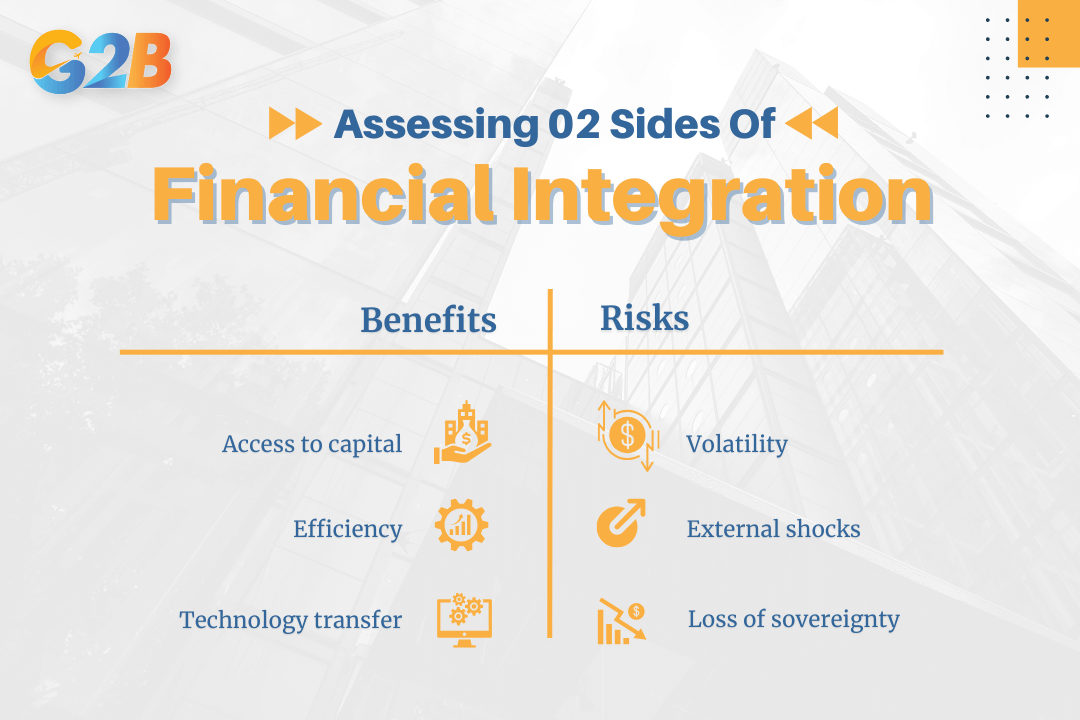

Assessing the two sides of financial integration

A high volume of transactions in the financial account signals deep financial integration with the global economy. This integration offers significant benefits but also exposes a country to considerable risks.

There are two sides of financial integration

Benefits

- Access to capital: Financial integration allows countries to fund investment opportunities beyond the limits of their domestic savings, which can accelerate economic growth and development.

- Efficiency: Global capital markets improve the allocation of capital by directing funds to where they can be used most productively, enhancing overall economic efficiency.

- Technology transfer: Foreign direct investment, a key component of the financial account, often brings with it advanced technologies, managerial expertise, and new skills, boosting the host country's productive capacity.

Risks

- Volatility: Portfolio investments, often called "hot money," can be withdrawn quickly, especially during times of uncertainty. Sudden and large-scale capital outflows can trigger financial instability, sharp currency devaluations, and economic crises.

- External shocks: A highly integrated economy is more susceptible to financial crises and economic downturns that originate in other parts of the world, a phenomenon known as contagion.

- Loss of sovereignty: Heavy reliance on foreign capital or significant foreign ownership of key domestic industries can constrain a government's ability to implement independent economic and monetary policies. The degree of this risk varies depending on the nature and scale of foreign investment and the regulatory framework of the host country.

The financial account is an indispensable lens through which to view a nation's economic standing and its intricate relationship with the global economy. It meticulously records the cross-border flow of investments, from stable, long-term direct investments to liquid and volatile portfolio flows. Its balance is fundamentally linked to the current account, as part of the overall Balance of Payments accounting, revealing whether a country is a net borrower from or a net lender to the rest of the world.

Delaware (USA)

Delaware (USA)  Vietnam

Vietnam  Singapore

Singapore  Hong Kong

Hong Kong  United Kingdom

United Kingdom