Fixed capital represents the bedrock of a company's entire operation, the long-term, tangible assets like machinery, buildings, and equipment that a company invests in to produce goods and services, not to sell directly to customers. While some business assets are fleeting and consumed in the daily churn of commerce, fixed capital forms the durable foundation upon which value is created year after year. This definitive guide will deconstruct fixed capital, exploring characteristics, differentiating it from working capital, and demonstrating its indispensable role in building a successful enterprise.

This article outlines the key aspects of fixed capital to help businesses and investors gain a clearer understanding. We specialize in company formation and do not provide financial or investment advisory services. For specific financial or legal matters, please consult a qualified financial advisor or relevant authority.

What is fixed capital?

Fixed capital refers to the tangible assets a business purchases for long-term use in its production process. Unlike inventory, which is bought to be sold quickly, fixed capital is acquired to help create what you sell. These assets are not expected to be converted into cash or consumed within a single accounting year. In accounting terms, these are often listed on the balance sheet under Non-Current Assets and are most commonly referred to as Property, Plant, and Equipment (PP&E).

Consider a bakery as an example. Ingredients such as flour and sugar are not classified as fixed capital since they are consumed on a daily basis. In contrast, the industrial ovens, mixers, and the building in which the bakery operates represent fixed capital. These are long-term assets that serve as essential tools for sustaining and operating the business.

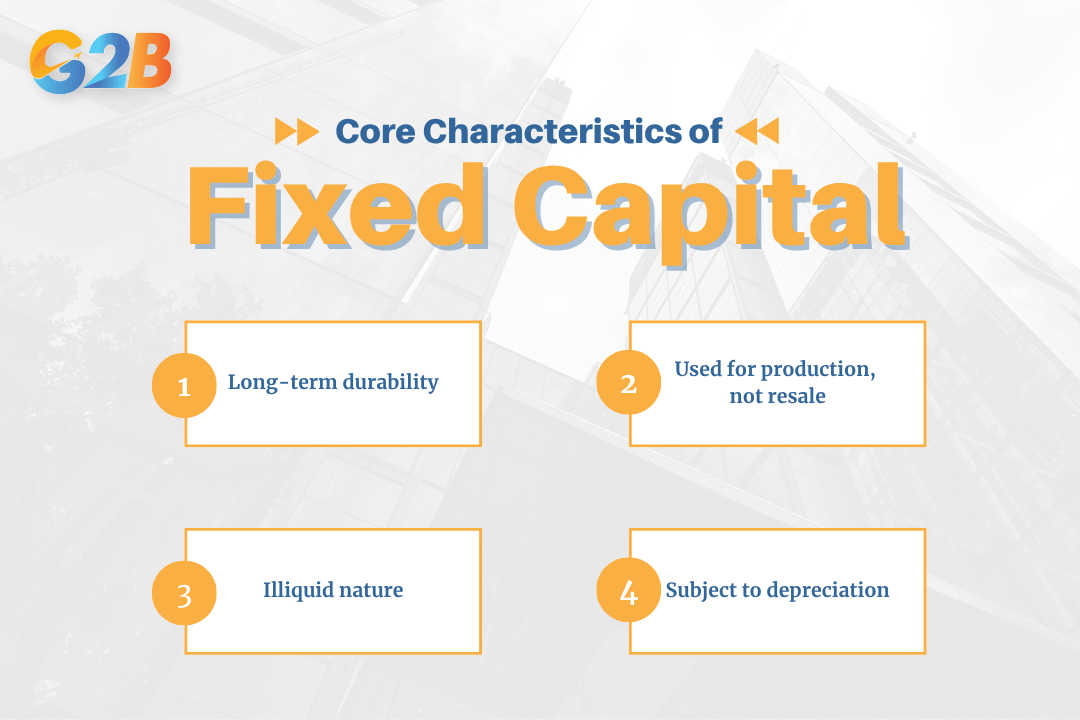

Core characteristics of fixed capital

To fully grasp the concept, it is essential to understand the four defining characteristics that distinguish fixed capital from all other types of business assets. These traits govern how it is financed, managed, and accounted for on the financial statements.

Long-term durability

The primary characteristic of fixed capital is its longevity. These assets are purchased with the expectation that they will provide economic value and contribute to operations for more than one accounting period, which is typically defined as over one year. Often, their useful life extends for many years or even decades, such as with buildings or heavy industrial machinery.

This long-term nature fundamentally contrasts with short-term assets, such as inventory or accounts receivable, which are expected to be converted into cash within a year. Fixed capital provides the stable, operational framework within which these short-term assets circulate, enabling sustained production and revenue generation over an extended period.

Used for production, not resale

Fixed capital is acquired for its utility within the business, not for speculative or resale purposes. Its purpose is to facilitate the core revenue-generating activities of the company, whether that involves manufacturing a product, delivering a service, or housing administrative functions. These are the tools of the trade, not the goods being traded.

A clear illustration of this is the distinction between two companies that both purchase vehicles. A car dealership buys a fleet of cars to sell to customers; for them, the cars are inventory. In contrast, a logistics company buys a fleet of trucks to deliver packages; for this company, the trucks are fixed capital because they are used in the service of the business over many years.

Illiquid nature

Liquidity refers to how quickly an asset can be converted into cash without a significant loss of value. By this measure, fixed capital is highly illiquid. Unlike cash in the bank or publicly traded stocks, you cannot sell a specialized manufacturing plant or an office building overnight at its fair market value.

This illiquidity stems from two factors: The specialized nature of the assets and the limited market of potential buyers. Selling a custom-built factory or a piece of proprietary equipment requires a lengthy process of finding a suitable buyer, negotiating terms, and transferring ownership. Because fixed assets cannot be easily liquidated to meet short-term cash needs, businesses must carefully manage their cash flow and working capital separately.

Subject to depreciation

With the notable exception of land, virtually all fixed capital assets lose value over their useful life. This decline in value is due to factors like physical wear and tear from use, technological obsolescence as newer models emerge, and general decay over time. This economic reality is recognized in accounting through the process of depreciation.

Depreciation is an accounting method used to allocate the cost of a tangible asset over its expected useful life. Instead of recording the entire expense of a machine in the year of purchase, depreciation spreads the cost of the asset over the years, which helps generate revenue. This provides a more accurate representation of a company's profitability and the asset's declining value on the balance sheet.

It is essential to understand the four defining characteristics that distinguish fixed capital from all other types of business assets

Examples of fixed capital

Fixed capital is not a single line item but a broad category encompassing the physical and, in some cases, non-physical assets that drive long-term value. Understanding these examples helps solidify the concept.

Tangible fixed assets

These are the physical, touchable items that form the backbone of a company's operations. They are most commonly categorized as Property, Plant, and Equipment (PP&E).

- Land and buildings: This includes all real estate owned by the company, such as corporate offices, warehouses, manufacturing plants, and retail storefronts.

- Machinery and equipment: This is a vast category covering everything from assembly line robots and industrial lathes to powerful computer servers, heavy construction equipment, and specialized manufacturing tools.

- Vehicles: Any vehicle used for business operations falls into this category, including company cars for salespeople, fleets of delivery trucks, forklifts for warehouse management, and even corporate aircraft.

- Furniture and fixtures: This includes all the internal components that furnish a business property, such as office desks, chairs, shelving units, point-of-sale counters, and retail display cases.

Intangible fixed assets

While the term "fixed capital" most often refers to tangible capital goods, some non-physical long-term assets are also categorized as non-current intangible assets but are not universally considered fixed capital. These are also considered non-current assets on the balance sheet.

- Patents and copyrights: These are exclusive legal rights granted for inventions or creative works, allowing a company to generate revenue from them over many years without competition.

- Trademarks and software: A valuable trademark or a proprietary software platform developed or purchased for long-term operational use represents a significant, non-physical asset crucial for business continuity and brand value.

Comparison between fixed capital and working capital

Fixed capital and working capital are two sides of the same coin; both are essential for a healthy business, but they serve fundamentally different and often opposing purposes. Confusing the two is a common and costly mistake in financial management, as each requires a distinct approach to funding and oversight. The table below clarifies the key distinctions.

| Feature | Fixed Capital | Working Capital |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Used to set up the business and for long-term production. | Used for day-to-day operations and short-term obligations. |

| Time Horizon | Long-term (Many years). | Short-term (Less than one year). |

| Liquidity | Low liquidity (hard to sell quickly). | High liquidity (cash or easily converted to cash). |

| Components | Machinery, Buildings, Land, Vehicles. | Cash, Inventory, Accounts Receivable. |

| Financing | Funded by long-term loans, equity, or bonds. | Funded by short-term loans, trade credit. |

Fixed capital formula and manage fixed capital

Managing fixed capital effectively is a cornerstone of corporate finance, involving strategic investment decisions (capital budgeting), efficient financing, and accurate tracking of asset value over time. While the total book value of fixed capital is readily found on the balance sheet under "Property, Plant, and Equipment (Net)," financial analysts often want to understand the change in this investment over a period.

Fixed capital formula and manage fixed capital

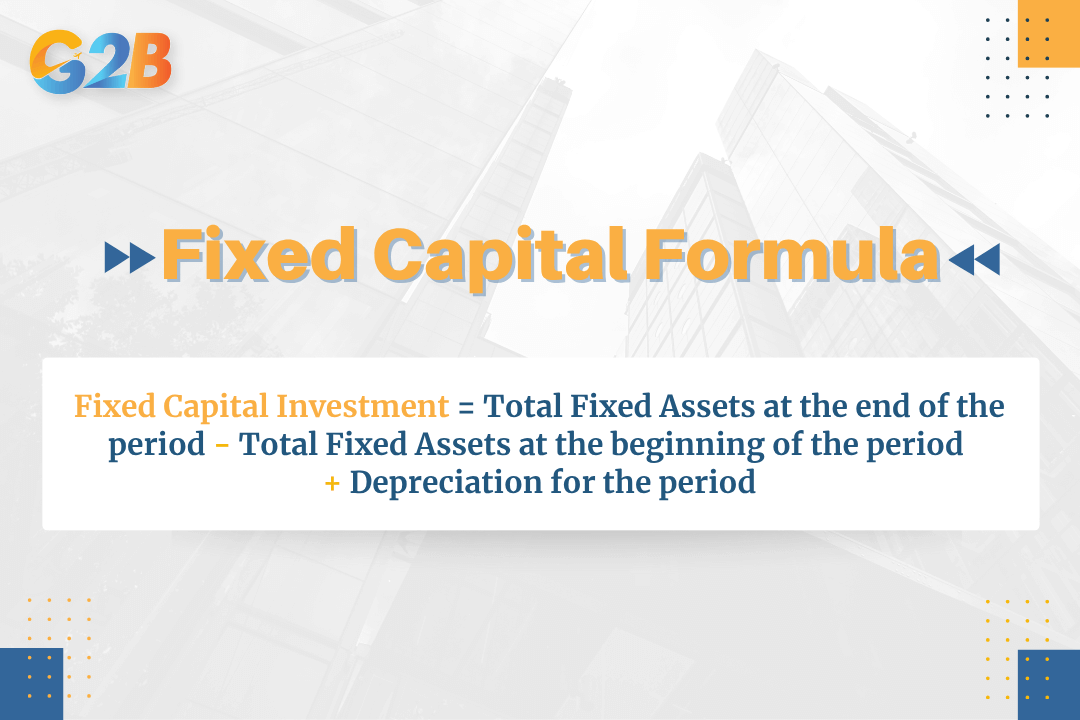

This change, known as net capital spending or Capital Expenditure (CapEx), reflects the company's commitment to maintaining or expanding its asset base. The formula to calculate this is:

Fixed Capital Investment = Total Fixed Assets at the end of the period - Total Fixed Assets at the beginning of the period + Depreciation for the period

In this formula, depreciation for the period is added back because it is a non-cash expense that reduces the book value of assets on the balance sheet. Adding it back reveals the actual cash spent on acquiring new fixed assets.

The role of depreciation

Depreciation is the central mechanism for managing the accounting value of fixed capital. Since valuable assets like machinery and buildings don't last forever, accounting principles forbid businesses from expensing the entire cost in the year of purchase. Doing so would drastically understate profit in the first year and overstate it in all subsequent years.

Instead, depreciation spreads the cost of the asset over its useful life. For example, if a company buys a delivery truck for $100,000 that is expected to last for 10 years with no salvage value, the simplest depreciation method (straight-line) would record a $10,000 depreciation expense each year. This method accurately matches the expense of using the asset with the revenues it helps generate and reflects the truck's declining value on the balance sheet. Other methods, such as the declining balance method, can be used to accelerate depreciation for assets that lose value more quickly in their early years, like computer equipment.

Sources of financing for fixed capital

Because investments in fixed capital, such as building a new factory or overhauling an IT system, require a large, lump-sum outlay of cash, they usually cannot be funded by a company's daily operational cash flow. Businesses must secure dedicated, long-term funding for these significant expenditures. There are three primary sources to finance fixed capital investments, each with its own set of trade-offs.

- Equity financing: This involves using the owner's capital or raising funds from external investors by selling ownership stakes (stock) in the company. The primary advantage is that this capital does not need to be repaid and comes with no interest expense. However, the major drawback is the dilution of ownership; the original owners will control a smaller percentage of the company. Sources can range from personal savings and angel investors for startups to a public stock offering for a large corporation.

- Long-term debt: This is the most common method and involves borrowing money that must be repaid with interest over an extended period. Sources include traditional bank loans, mortgages specifically for real estate, and issuing corporate bonds to the public. The main benefit is that owners retain full control and ownership of the company. The downside is the obligation to make regular interest and principal payments, which adds financial risk (leverage) and can come with restrictive covenants from lenders.

- Leasing: Instead of buying an asset outright, a company can choose to lease it for a specified period. This is particularly common for assets that become obsolete quickly, such as technology, or for assets that require immense upfront capital, like aircraft. Leasing requires much less initial cash, preserving capital for other needs. The key disadvantage is that the company builds no equity and does not own the asset at the end of the lease term (unless it's a finance lease with a purchase option).

Contrast with common misconceptions

To sharpen your understanding, it is important to clarify what fixed capital is not. Misclassifying assets is a frequent source of error in financial analysis and strategic planning, leading to a skewed view of a company's liquidity and operational structure.

- Is inventory fixed capital?

- No. Inventory, which includes raw materials, work-in-progress, and finished goods, is the lifeblood of a company's sales cycle. It is intended to be sold or consumed as quickly as possible. It is the core component of working capital.

- Is cash fixed capital?

- No. Cash is the most liquid asset a company possesses and is the primary tool for settling daily expenses and short-term liabilities. It is the definitive component of working capital.

- Are all investments fixed capital?

- No. The purpose of the asset is key. If a manufacturing company buys stocks or bonds in another company, intending to sell them within a year for a profit, that is a short-term financial investment. It is not fixed capital because it is not being used in the company's own production process.

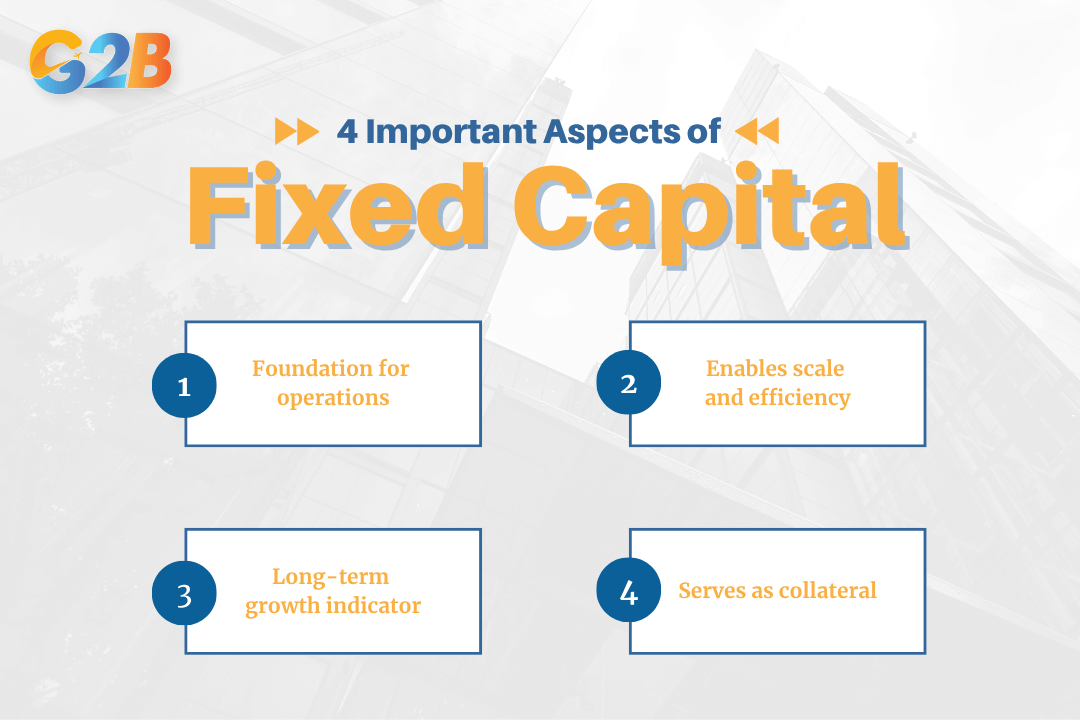

Importance of fixed capital in business

Fixed capital is far more than just a collection of assets or a line item on a balance sheet; it is a strategic enabler and a powerful engine for any business with ambitions beyond mere survival. Its importance can be seen across four critical dimensions of business success.

There are 4 important aspects of fixed capital in business

- Foundation for operations: At the most basic level, fixed capital makes business possible. A manufacturing company simply cannot operate without a factory and the machines within it. A logistics company is non-existent without its fleet of trucks and network of warehouses. A modern software company is powerless without its servers and data centers. Fixed capital provides the essential physical and technological infrastructure required to produce goods and deliver services.

- Enables scale and efficiency: Strategic investment in fixed capital is the primary driver of economies of scale. By acquiring better, more modern, or larger-capacity assets, such as automated assembly lines, advanced software, or more fuel-efficient vehicles, a company can dramatically increase its production capacity and operational efficiency. This lowers the cost per unit of output, boosts profit margins, and creates a significant competitive advantage over rivals with an inferior asset base.

- Long-term growth indicator: For investors, analysts, and lenders, a company's pattern of investment in fixed capital is a powerful signal of its future prospects. Consistent and intelligent capital expenditure (CapEx) demonstrates that management is confident in future demand and is actively planning for growth and expansion. Conversely, a company that fails to reinvest in its asset base is often seen as stagnant or in decline, risking operational failures as its equipment ages and becomes obsolete.

- Serves as collateral: The significant, tangible value of fixed assets like land, buildings, and heavy equipment makes them excellent collateral for securing debt. By pledging these assets, a business can gain access to larger amounts of capital from banks and other lenders, often at more favorable interest rates. This ability to leverage its fixed asset base gives a company greater financial flexibility to seize growth opportunities, navigate economic downturns, and fund further expansion.

Fixed capital is the enduring skeleton upon which the muscle of a business is built. It encompasses the long-term, illiquid assets, the machinery, buildings, and technology, that are used for production rather than for immediate sale. This fundamentally distinguishes it from the fluid, short-term nature of working capital, which manages the day-to-day operational cycle. Understanding this distinction is crucial for sound financial management, especially for entrepreneurs planning to register a company in Vietnam and establish a solid operational foundation.

Delaware (USA)

Delaware (USA)  Vietnam

Vietnam  Singapore

Singapore  Hong Kong

Hong Kong  United Kingdom

United Kingdom