A fixed exchange rate is a tool used by governments and central banks to provide currency stability in a global market. A stable and predictable currency is the bedrock of international trade and investment, and for many countries, achieving this stability means abandoning the volatile whims of the open market and adopting this system, which comes with its own unique set of rules, benefits, and risks. This stability can be particularly important for foreign investors looking to register a company in Vietnam, as it helps reduce exchange rate uncertainty in cross-border transactions. This comprehensive guide will break down what a fixed exchange rate is, how it works, and its different forms.

This article outlines the key aspects of the fixed exchange rate system to help businesses and investors gain a clearer understanding. We specialize in company formation and do not provide financial or monetary policy advice. For regulatory or legal matters, please consult a qualified financial advisor or the relevant authority.

What is a fixed exchange rate?

A fixed exchange rate, also known as a pegged exchange rate, is a currency management system where a country's government or central bank sets and maintains an official exchange rate for its currency. The value is "pegged" or "fixed" to the value of another country's currency (like the U.S. dollar), a basket of several currencies, or a commodity like gold.

Unlike a floating rate that fluctuates based on market supply and demand, a fixed rate is held constant by the central bank's intervention. This intervention involves actively buying or selling its own currency using foreign exchange reserves to maintain the peg. The primary goal is to provide economic stability and predictability, making it easier for businesses to conduct international trade and for investors to make financial decisions without worrying about currency fluctuations. This certainty helps the government maintain low inflation and can stimulate trade and investment.

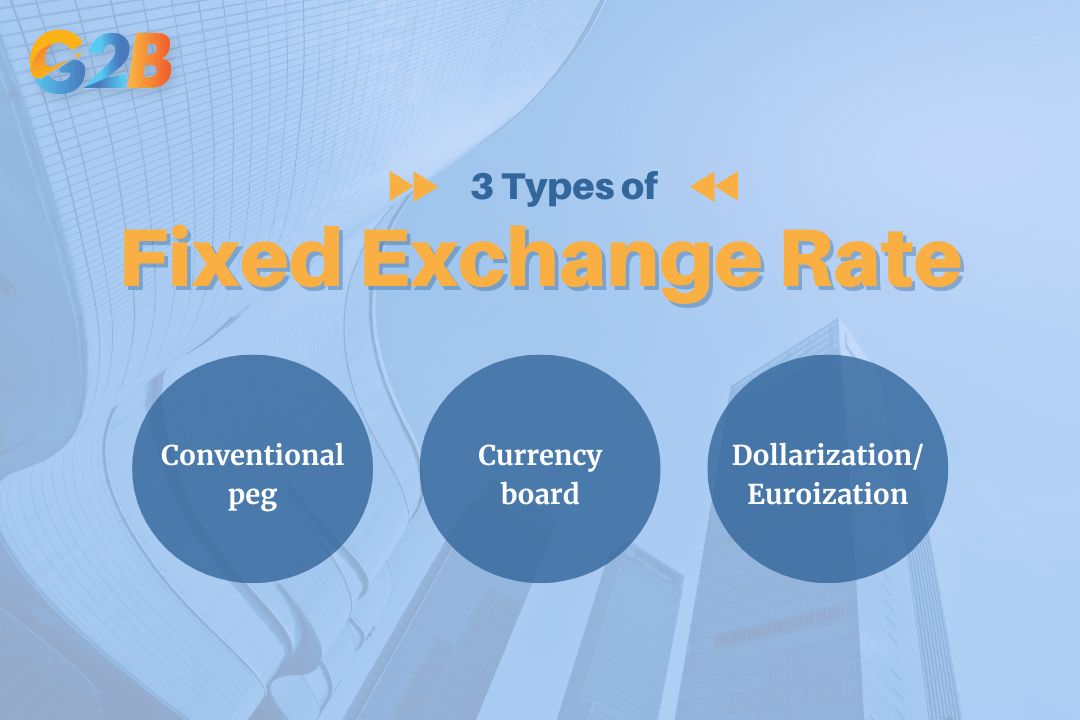

Types of fixed exchange rate

While the core idea is the same, fixed exchange rate systems exist on a spectrum from flexible pegs to the complete adoption of a foreign currency. These systems are broadly divided into hard pegs and soft pegs, with hard pegs being the most rigid.

Fixed exchange rate systems exist on a spectrum from flexible pegs to the complete adoption of a foreign currency

1. Conventional peg

This is the most common form of a soft peg. A country pegs its currency to another major currency (or a basket) and allows the exchange rate to fluctuate within a very narrow band, such as ±1% or ±2.25%. The central bank actively intervenes in the foreign exchange market to ensure the currency's value stays within this predetermined band. This system provides stability but requires constant vigilance and significant foreign reserves to manage.

2. Currency board

This is a stricter, more rigid system known as a "hard peg." A currency board is an arrangement that legally requires the country to back every unit of its domestic currency with an equivalent amount of foreign currency reserves. For example, to issue 10 of its own currency units, the central bank must hold the equivalent U.S. dollar value in its reserves. This creates immense credibility and discipline but eliminates any monetary policy independence, as the domestic money supply is directly tied to the foreign reserves on hand. The Hong Kong Dollar, which is pegged to the U.S. dollar, is a prime example of a successful currency board.

3. Dollarization/Euroization

This is the most extreme form of a fixed rate system. In this case, a country completely abandons its own currency and adopts a foreign currency as its legal tender. For example, Ecuador, Panama, and El Salvador use the U.S. dollar. This process is known as full dollarization. This provides the ultimate stability and eliminates the risk of a currency crisis, as there is no domestic currency to attack. However, it means the country completely cedes control of its monetary policy to the foreign central bank (e.g., the U.S. Federal Reserve or the European Central Bank).

How does a fixed exchange rate system work?

The mechanism behind a fixed exchange rate relies on the country's central bank and its stockpile of foreign exchange reserves. The central bank becomes the ultimate buyer and seller of its currency to ensure the price stays at the pegged level. This is achieved through open market operations, where the central bank buys or sells currencies to influence supply and demand.

How a fixed exchange rate system works in two scenarios

Here’s how it works in two scenarios:

- Scenario 1: The currency is getting too strong (appreciating).

- Problem: High demand for the local currency, often due to strong exports or foreign investment, pushes its market value above the fixed rate. This creates an excess demand for the currency.

- Central Bank Action: To weaken its currency and bring the rate back down to the peg, the central bank sells its own currency in the foreign exchange market and buys the foreign currency it's pegged to. This action increases the supply of its own currency, satisfying the excess demand and reducing its market price back to the target level.

- Scenario 2: The currency is getting too weak (depreciating).

- Problem: Low demand for the local currency, perhaps due to rising imports or capital flight, pushes its market value below the fixed rate. This creates an excess supply of the currency.

- Central Bank Action: To strengthen its currency and bring the rate back up, the central bank uses its foreign exchange reserves. It buys its own currency from the market using its holdings of the foreign currency (e.g., U.S. dollars). This decreases the supply of its currency, increasing its price back toward the peg.

The key takeaway: A country must have sufficient foreign reserves to "defend" its peg. If a central bank runs out of foreign reserves, it can no longer support its currency's value by buying it back. This can lead to a forced devaluation or a collapse of the peg, potentially triggering a financial crisis.

Fixed vs. Floating exchange rate

Understanding a fixed exchange rate is easiest when comparing it directly to a floating exchange rate. The fundamental difference lies in how the value of a currency is determined.

| Feature | Fixed Exchange Rate | Floating Exchange Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Determination | Set and maintained by the government or central bank at a specific level against another currency or a commodity. | Determined by market forces of supply and demand in the foreign exchange market. |

| Stability | High. Provides certainty and predictability for trade, investment, and financial planning. | Low. Can be volatile and change constantly based on economic conditions, interest rates, and investor sentiment. |

| Monetary Autonomy | Low. The central bank must use its monetary policy tools, primarily interest rates, to defend the peg. It cannot independently address domestic economic issues like inflation or recession. | High. The central bank is free to set interest rates to control domestic inflation, combat a recession, or manage unemployment. |

| Central Bank's Role | Active. Constant monitoring and intervention are required to buy or sell currency to maintain the pegged rate. | Passive. The central bank generally lets the market set the rate, though it may occasionally intervene to prevent extreme volatility (a system known as a managed float). |

| Vulnerability | Prone to speculative attacks. Investors may bet against the central bank's ability to maintain the peg, leading to a currency crisis if reserves are depleted. | Absorbs economic shocks through price changes. The currency can depreciate to make exports cheaper and imports more expensive, acting as an automatic stabilizer. |

Frequently asked questions

The fixed exchange rate system often raises many practical and technical questions among businesses, investors, and policymakers. To help better understand how it works and what implications it may have for international transactions, these are answers to some of the most common questions below.

Q1: Can a fixed exchange rate change?

A: Yes, it can. While intended to be stable, a government can officially change a fixed exchange rate through a deliberate policy decision. A devaluation occurs when the monetary authority lowers the official fixed value of its currency, making it cheaper relative to the foreign currency it is pegged to. A revaluation is the opposite, where the government increases the official rate, making its currency more expensive. These actions are typically undertaken to correct long-term economic imbalances, improve export competitiveness, or respond to major economic shocks.

Q2: Is the Chinese Yuan a fixed exchange rate?

A: Not strictly. China uses a hybrid system often called a managed float or a crawling peg. The People's Bank of China (PBOC) sets a daily "reference rate" for the Yuan against a basket of currencies. The Yuan is then allowed to trade within a narrow band (e.g., ±2%) around that rate. This system gives the Chinese government more control over its currency's value than a freely floating system, allowing it to manage trade competitiveness, but offers more flexibility than a rigid fixed peg.

Q3: Why would a country choose a fixed exchange rate?

A: A country typically chooses a fixed exchange rate for several key reasons, centered on achieving economic stability and credibility. The main motivations include:

- To Promote Stability and Predictability: It eliminates currency risk, which encourages foreign investment and simplifies international trade by providing certainty for importers and exporters.

- To Control Inflation: By pegging to a stable, low-inflation currency like the U.S. dollar or the Euro, a country effectively "imports" the monetary discipline of that currency's central bank. This helps anchor inflation expectations and build confidence.

- To Build Credibility: For developing nations or economies with a history of monetary instability, a fixed rate can signal a strong commitment to stable and predictable economic policies.

Q4: Is a fixed or floating exchange rate better?

A: There is no single "better" system; the ideal choice depends entirely on a country's economic circumstances, size, and policy priorities. The decision represents a fundamental trade-off between stability and flexibility.

- Fixed rates are often favored by smaller, developing economies that are heavily reliant on trade and need to build credibility and stability to attract foreign investment.

- Floating rates are generally preferred by large, diversified, and mature economies (like the U.S., Japan, and the UK) because they provide monetary policy independence. This flexibility allows the central bank to respond to domestic economic needs, such as managing inflation or combating unemployment, without being constrained by the need to defend a currency peg.

A fixed exchange rate system offers a powerful promise of stability in an often-volatile global economy. Its primary function is to eliminate currency uncertainty, thereby fostering international trade and investment. This stability is achieved through the diligent and active intervention of a nation's central bank, which uses its foreign reserves to maintain a pegged value against another currency or asset. However, this stability comes at a significant cost: The loss of monetary policy autonomy. The choice between a fixed rate's predictability and a floating rate's flexibility is a critical policy decision that profoundly shapes a country's economic path and its relationship with the global market.

Delaware (USA)

Delaware (USA)  Vietnam

Vietnam  Singapore

Singapore  Hong Kong

Hong Kong  United Kingdom

United Kingdom